Implementation of Ultraviolet / H2O2 Treatment for inactivation of microorganisms

and pesticide control

ABSTRACT

N.V. PWN Water Supply Company North Holland will replace breakpoint chlorination at their Andijk

drinking water treatment plant. Major objectives are restriction of disinfection by-product formation,

increased pathogen inactivation and multiple barriers for organic contaminant control.

The aim of this study was to show the feasibility of Ultraviolet / H2O2 treatment for primary disinfection and

pesticide control in direct surface water treatment.

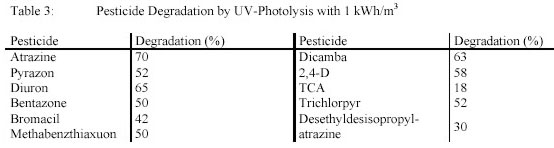

For 12 priority pesticides conversion by Ultraviolet photolysis and hydroxyl radical reactions were studied. Ultraviolet

photolysis gives a selective degradation, hydroxyl radical reactions were more aselective. These findings

were confirmed in pilot plant studies. For an electric energy of 1 kWh/m3 conversion varied from 18 % for

trichloroacetic acid to 70 % for atrazine. For a combination of  1 kWh/m3 and 1 kWh/m3 and  15 g/m3 H2O2 all

pesticides could be degraded for more than 80 %. At this conversion of 80 % metabolite formation was

insignificant, while no bromate formation was found.

A 2 3 log inactivation of Giardia muris and Cryptosporidium parvum was achieved by an Ultraviolet dose of

20 mJ/cm2. For a complete inactivation of all micro-organisms an Ultraviolet dose up to 105 mJ/cm2 was

required.

Reactivation of protozoa was established for an Ultraviolet dose up to 25 mJ/cm2. For doses higher than

60 mJ/cm2 no reactivation was observed.

Based on quantum yields, reaction rate constants, CFD modelling and pilot plant experiments it was

shown that 80 % pesticide degradation can be achieved with a proper combination of electric energy and

hydrogen peroxide. The electric energy for pesticide degradation is much higher than required for

disinfection. Residual H2O2 removal and AOC control are achieved by GAC filtration. 15 g/m3 H2O2 all

pesticides could be degraded for more than 80 %. At this conversion of 80 % metabolite formation was

insignificant, while no bromate formation was found.

A 2 3 log inactivation of Giardia muris and Cryptosporidium parvum was achieved by an Ultraviolet dose of

20 mJ/cm2. For a complete inactivation of all micro-organisms an Ultraviolet dose up to 105 mJ/cm2 was

required.

Reactivation of protozoa was established for an Ultraviolet dose up to 25 mJ/cm2. For doses higher than

60 mJ/cm2 no reactivation was observed.

Based on quantum yields, reaction rate constants, CFD modelling and pilot plant experiments it was

shown that 80 % pesticide degradation can be achieved with a proper combination of electric energy and

hydrogen peroxide. The electric energy for pesticide degradation is much higher than required for

disinfection. Residual H2O2 removal and AOC control are achieved by GAC filtration.

In view of the very promising results PWN will install Ultraviolet / H2O2 at their Andijk plant. Three streets of

4 Trojan Swift 16L30 reactors will be installed before the middle of 2004.

INTRODUCTION

In 1920, when N.V. PWN Water Supply Company North Holland (PWN) was founded, the demand for

drinking water was satisfied by ground water extraction . However by the growing drinking water demand

PWN was compelled to utilize surface water as an additional source.

Therefore in the 1960's water treatment plant Andijk was constructed for the direct production of drinking

water from IJssel Lake (River Rhine) water. Originally the plant consisted of microstraining, breakpoint

chlorination, coagulation, sedimentation, rapid filtration and post disinfection. In 1978 the plant was

upgraded with a pseudo moving bed GAC filtration.

After about 40 years of operation, wtp Andijk still complies with all Dutch drinking water standards.

Nevertheless an upgrade is desired in view of by-product (THM) formation and the barriers against

pathogenic micro-organisms such as protozoa and organic micropollutants such as pesticides.

PWN has pursued the application of advanced oxidation for both primary disinfection and organic

contaminant control followed by the already present GAC filtration for removal of residual H2O2 and AOC

with very promising results. Ultraviolet / H2O2 will be installed and become operational mid 2004.

PROCESS SELECTION

PWN's aim was to select an oxidative process able to inactivate pathogenic micro-organisms and to

degrade pesticides aselectively with a restricted by-product formation compared to breakpoint

chlorination.

Initially the focus was on ozone based technologies. (1) Ozone was able to achieve the required

disinfection capacity. However ozone proved to be a selective barrier against pesticides.

In advanced oxidation technologies hydroxyl radicals react 106 to 109 times faster than ozone, causing a

much more aselective pesticide degradation.

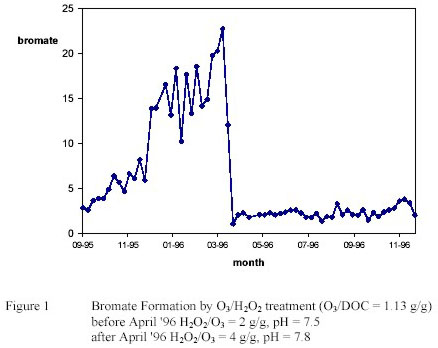

O3/H2O2 treatment proved to be a sound barrier against pesticides. In pretreated IJssel Lake water 80 %

pesticide degradation could be achieved by an O3 dose of 2.8 g/m3 and a H2O2/O3 ratio of 2 g/g. (2)

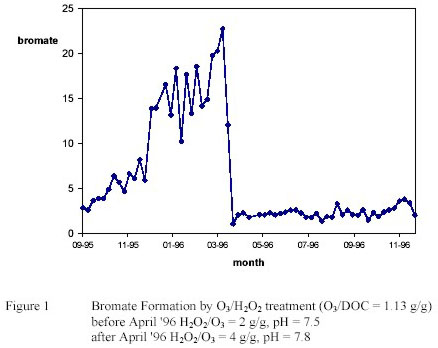

However bromate was found at high levels especially at low water temperature. (3) Feasible treatment

options (increase H2O2/O3 ratio, increase pH) could not control bromate formation completely caused by

mass transfer limitations. (see figure 1) (3)

Under optimal conditions for pesticide and bromate control disinfecting properties of the O3/H2O2 process

were very poor. Corresponding with high H2O2/O3 ratios and very low c.t. values for ozone, inactivation

of spores of sulphite reducing clostridia was insignificant. (4)

In view of these findings PWN rejected O3/H2O2 treatment for primary disinfection and pesticide control

at wtp Andijk and decided to pursue alternative strategies with the focus on Ultraviolet technologies.

PHOTOLYSIS AND ADVANCED OXIDATION BY ULTRAVIOLET / H2O2 TREATMENT

Ultraviolet photolysis is based on the absorption of Ultraviolet photons by contaminants to cause their degradation into

smaller products. The absorbed energy must be higher than the energy of the band to be broken to cause

photolysis.

In addition to the absorption of Ultraviolet photons the quantum yield of the degradation is an important

parameter. Compounds with a high Ultraviolet absorbance and a high quantum yield are very susceptible to

photodegradation. (5)

However not all substances absorb Ultraviolet light significantly or have a high quantum yield. In order to

promote a more aselective degradation H2O2 may be added to produce hydroxyl radicals.

The general expression for the degradation rate of a contaminant is a combination of direct Ultraviolet photolysis

and hydroxyl radical reactions:

Not too many  and kC,OH values for pesticide degradation are given in literature. An electric energy of

0.5 kWh/m3 is reported for 60 % atrazine photolysis. Under these conditions pesticide degradation varied

from 18 % for dicamba to 92 % for mecoprop. (6) Additional research is needed to determine quantum

yield and hydroxyl radical rate constants for representative organic micropollutants and to determine the

process conditions for Ultraviolet / H2O2 treatment with medium pressure Ultraviolet lamps. and kC,OH values for pesticide degradation are given in literature. An electric energy of

0.5 kWh/m3 is reported for 60 % atrazine photolysis. Under these conditions pesticide degradation varied

from 18 % for dicamba to 92 % for mecoprop. (6) Additional research is needed to determine quantum

yield and hydroxyl radical rate constants for representative organic micropollutants and to determine the

process conditions for Ultraviolet / H2O2 treatment with medium pressure Ultraviolet lamps.

Disinfection by Ultraviolet

There is an abundance of literature on the inactivation of fecal coliform bacteria by Ultraviolet radiation. It has

been known for some time that viruses and spore forming bacteria are more resistant to the effect of Ultraviolet

radiation than coliform bacteria. Chang et al (7) showed that viruses, bacterial spores and amoebic cysts

required 3 4 times, 9 times and 15 times more Ultraviolet exposure to achieve the same level of inactivation as

Escherichia coli.

It had been thought that encysted protozoa were insensitive to Ultraviolet.(8,9) More recent studies have shown

that encysted Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia muris are relatively sensitive to Ultraviolet radiation. (10, 11,

12)

Reactivation of pathogenic micro-organisms is a critical parameter with the respect to the treatment of

drinking water. It is well known that select pathogenic micro-organisms are capable of reactivating after

exposure to Ultraviolet light. Mechsner et al (13) demonstrated that E coli inactivated by low pressure Ultraviolet

repaired its DNA after several days incubation in the dark.

More work is needed to determine the overall reactivation potential of water-borne pathogenic microorganisms

of concern to the water industry.

The ultimate goal for Ultraviolet disinfection of drinking water is to damage DNA beyond repair.

Additional research is needed to establish dose-response curves for several pathogenic micro-organisms

and to establish the Ultraviolet dosage where DNA is damaged beyond repair.

OBJECTIVES

Disinfection

Three major objectives were pursued in a collaborative study carried out by the University of Alberta and

PWN:

- to select representative organisms and characterize Ultraviolet inactivation by generating Ultraviolet doseinactivation

curves for MS2 phages, Bacillus subtilis endospores, Giardia muris cysts and

Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts using a bench scale collimated beam apparatus;

- to determine the ability of one small medium pressure Ultraviolet reactor and three larger medium pressure

Ultraviolet reactors to inactivate MS2 phages, Bacillus subtilis endospores, Giardia muris cysts and

Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts;

- to examine the reactivation of Giardia muris and Cryptosporidium parvum ex-vivo and in vivo and to

determine more precisely the Ultraviolet dose required for inactivation of these protozoan parasites in

drinking water.

Organic contaminant control

Three additional major objectives were pursued by PWN, partly in collaboration with Trojan

Technologies Inc.:

- to select representative organic micropollutants (pesticides) and characterize degradation by Ultraviolet

photolysis and hydroxyl radical reaction for 12 selected pesticides;

- to predict and determine the ability of a medium pressure Ultraviolet reactor to degrade those 12 priority

pollutants;

- to design a full scale Ultraviolet / H2O2 system for both disinfection and organic contaminant control.

Posttreatment

Two additional objectives were pursued by PWN to integrate Ultraviolet / H2O2 treatment in the total treatment

scheme:

- the removal of excess H2O2 by GAC filtration;

- the removal of AOC by GAC filtration.

INACTIVATION OF MICRO-ORGANISMS

Bench scale experiments.

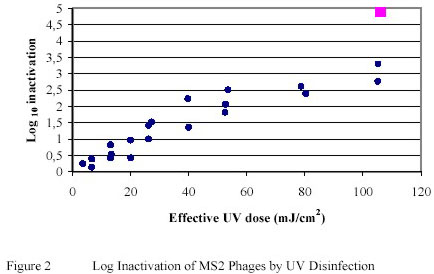

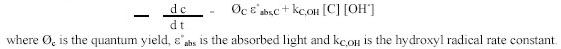

The bacteriophage MS2 has been shown to be relatively resistant to Ultraviolet inactivation. A reduction of approximately 1 log-unit was achieved when MS2 phages, suspended in PWN water, was exposed to Ultraviolet doses of 20 25 mJ/cm2. (Figure 2)

The correlation between log inactivation and effective Ultraviolet dose demonstrated a near linear relationship,

particularly within the Ultraviolet dose range of up to 50 mJ/cm2. This contrasts the Ultraviolet inactivation curves

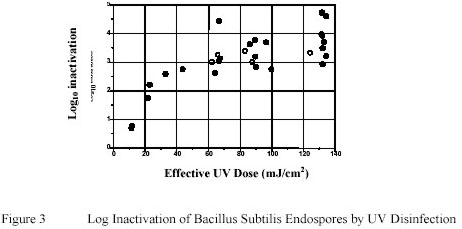

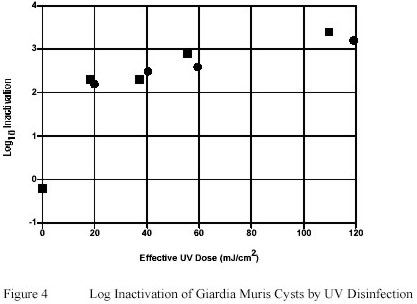

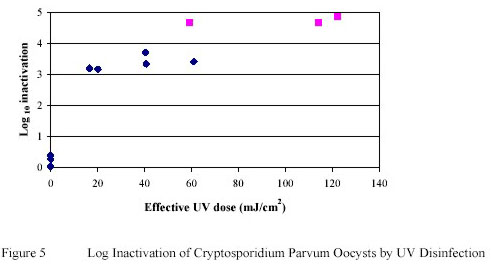

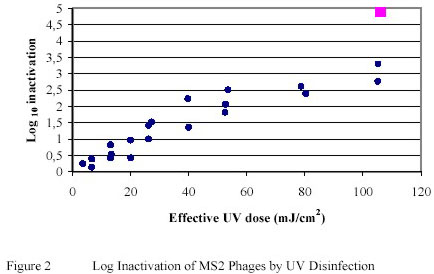

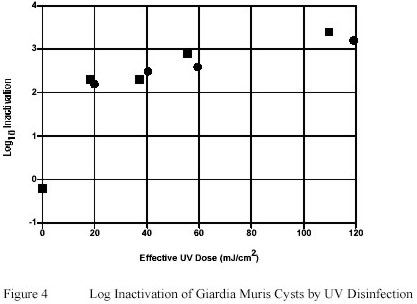

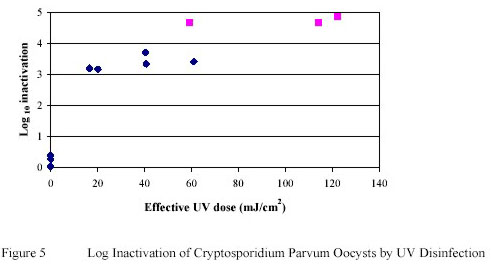

obtained for Bacillus subtilis (Figure 3), Giardia muris (Figure 4) and Cryptosporidium parvum (Figure 5)

where distinct shouldering and tailing effects were observed.

Figure 3 summarizes the results to determine the effect of Ultraviolet inactivation on Bacillus subtilis endospores

suspended in PWN water. Similar to data reported by Sommer and Cabaj (14) a distinct shouldering effect

was observed when endospores were exposed to Ultraviolet doses less than 20 mJ/cm2.

However, unlike the data presented by Sommer and Cabaj a pronounced tailing effect was observed.

Sommer and Cabaj reported a log reduction of approximately 4 log units with Ultraviolet doses of 60 mJ/cm2. In

this study 3 log and 4 log reduction were achieved at about 60 and 120 mJ/cm2 respectively.

Giardia muris cysts suspended in PWN water were shown to be relatively susceptible to Ultraviolet inactivation.

An Ultraviolet dose of as low as 20 mJ/cm2 induced greater than 2 log-unit inactivation of Giardia muris.

However a pronounced tailing effect in the ability of Ultraviolet to inactivate the infective potential of Giardia

muris cysts was observed with Ultraviolet doses greater than 20 mJ/cm2. (Figure 4).

Exposure of Giardia muris cysts to Ultraviolet doses as high as 120 mJ/cm2 resulted in only 1 additional log-unit

of inactivation compared to Ultraviolet doses of 20 mJ/cm2 only.

Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts suspended in PWN water were extremely susceptible to low doses of

Ultraviolet. Greater than a 3 log-unit reduction in oocyst infectivity was observed in trials where oocysts were

exposed to Ultraviolet doses as low as 20 mJ/cm2. For Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts the tailing effect of the

Ultraviolet dose-inactivation curve was not as pronounced as that observed for Giardia muris cysts (Figure 5).

Ultraviolet doses of approximately 120 mJ/cm2 induced greater than 4.5 log-units of inactivation. สเ๒เ๋๎ใ ํ๎๐๊๎โ๛๕ ๘๓แ ๖ๅํ๛

However, the presence of the tailing suggests that a Ultraviolet resistant sub-population of oocysts may be present

within any given batch of oocysts, which remains to be confirmed using molecular analysis of the resistant

sub-population of the (oo)cysts.

Pilot plant experiments

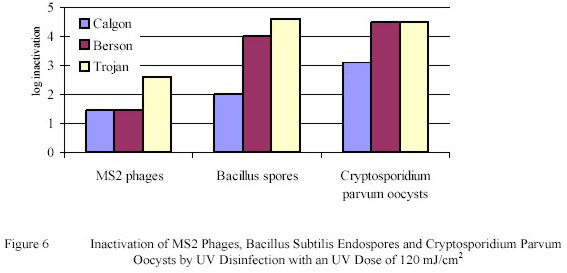

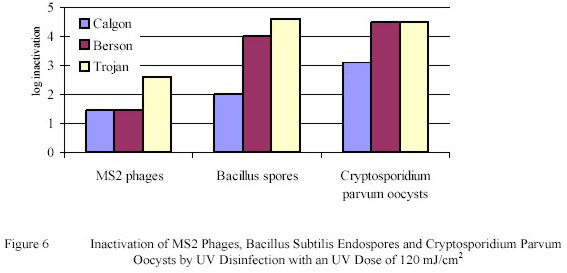

The collimated beam data demonstrate that medium pressure Ultraviolet radiation effectively inactivated MS2

phages, Bacillus subtilis endospores, Giardia muris cysts and Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts suspended

in pretreated IJssel Lake water. The results were confirmed by data obtained with a small scale Berson Ultraviolet

reactor and with three larger scale reactors from Calgon, Berson and Trojan. Of the three larger scale Ultraviolet

reactors the Berson and Trojan reactors showed inactivation levels equivalent to the collimated beam

experiments, while the Calgon unit showed a lower inactivation level (Figure 6).

The findings show that Ultraviolet disinfection is a very reliable technology for the inactivation of pathogenic

micro-organisms in drinking water. A Ultraviolet dose of 105 mJ/cm2 gives a high inactivation of phages and

endospores and a complete inactivation of protozoan cysts and oocysts.

REACTIVATION OF MICRO-ORGANISMS

It is important to understand that it is debatable as to whether or not Ultraviolet-irradiation causes permanent or

temporary inactivation of micro-organisms. Relatively little is known about the repair of Ultraviolet-damaged

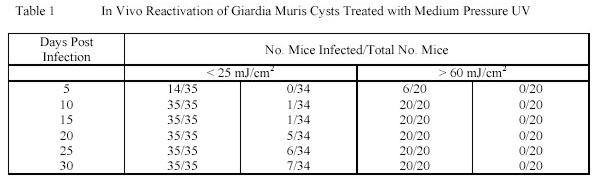

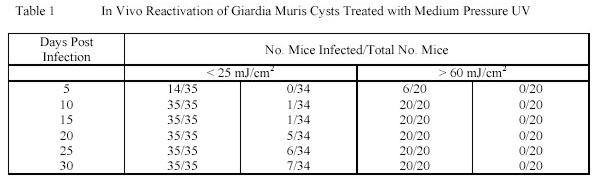

DNA in encysted water-borne protozoan pathogens. Our data indicated that neither Giardia muris cysts

nor Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts are capable of in vitro reactivation. The results for in vivo

reactivation of Giardia muris cysts are summarized in table 1.

From the data it can be concluded that Giardia muris cysts are capable of in vivo reactivation after Ultraviolet

treatment when the Ultraviolet dose applied is as low as 25 mJ/cm2. This dose is significantly lower than the Ultraviolet

dose of 105 mJ/cm2 needed for a 3.5 log-unit inactivation of MS2 phages.

For Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts the in vivo repair could not be tested due to the "end-point" animal

model.

DEGRADATION OF ORGANIC MICROPOLLUTANTS

Bench Scale Experiments in Pretreated IJssel Lake Water

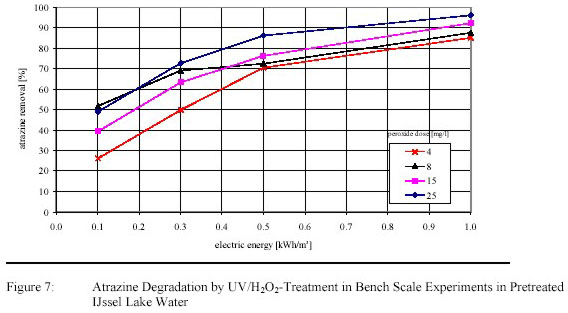

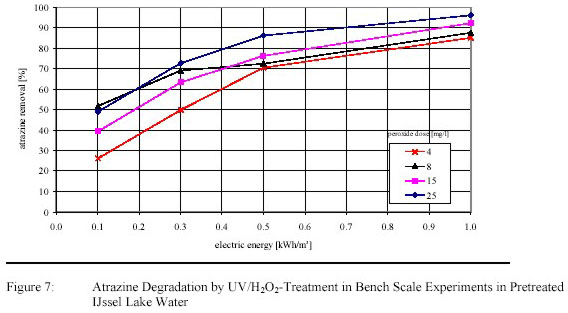

Four test runs were carried out with pretreated IJssel Lake water for a first optimization of electric energy

input and H2O2-dosage. Atrazine degradation is presented in figure 7.

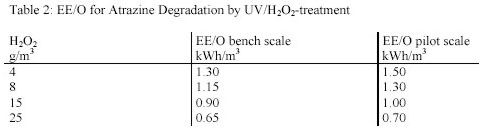

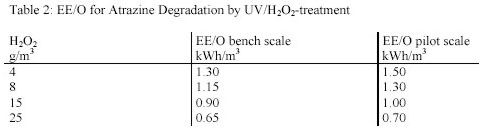

The EE/O was ranging from 0.65 1.30 kWh/m3 depending on the H2O2-dose (see Table 2).

Under no reaction conditions bromate formation was found.

Because the process was considered as cost effective pilot plant research was carried out.

Pilot Plant Experiments Phase 1

Four test runs were carried out with new Ultraviolet lamps under conditions corresponding with the bench scale

experiments.

Atrazine conversion in bench and pilot plant scale testing was in the same order of magnitude.

(see Table 2)

The range of EE/O values for pilot testing was only slightly higher than for bench scale testing:

0.70 1.50 kWh/m3 and 0.65 1.30 kWh/m3 respectively.

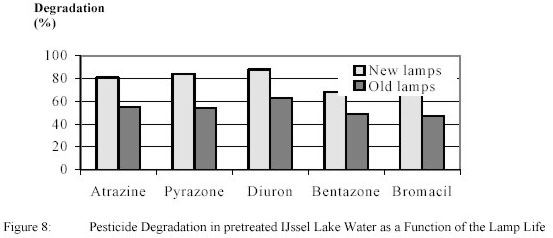

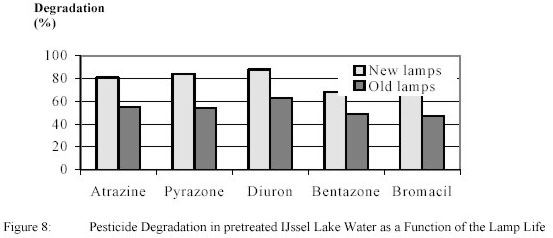

Two conditions being 0.6 kWh/m3 + 15 g/m3 H2O2 and 0.9 kWh/m3 + 4 g/m3 H2O2 were chosen for further

research with five selected priority pollutants: atrazine, pyrazone, diuron, bentazone and bromacil. The

experiments were carried out with new lamps and after a lamp life of 2000 h.. The results for 0.9 kWh/m3

+ 4 g/m3 H2O2 are shown in figure 8.

For new lamps pyrazone and diuron were degraded slightly higher than atrazine, while bentazone and

bromacil conversion were slightly lower.

After 2000 burning hours pesticide degradation dropped significantly and amounted roughly

50 % of the original degradation. Lamp control showed that the Ultraviolet-output of the lamps was decreased by

23 68 % showing that, in addition to electric energy data, measurement of Ultraviolet-dose is urgently needed.

Irrespective of reaction conditions no bromate was found.

Ultraviolet extinction dropped with 20 %, DOC-removal was insignificant.

AOC increased from 10 ตg/l to 110 140 ตg/l. Therefore biological stability after Ultraviolet / H2O2-treatment is

an important issue.

Ultraviolet / H2O2-treatment enables 80 % pesticide degradation without a significant formation of primary

pesticide metabolites and bromate. Until now the experiments were focused on the combined effect of

Ultraviolet-photolysis and hydroxyl radical oxidation. In the second phase of the pilot plant research the effect of

Ultraviolet-photolysis only followed by the additional effect of advanced oxidation was studied.

Pilot Plant Experiments Phase 2

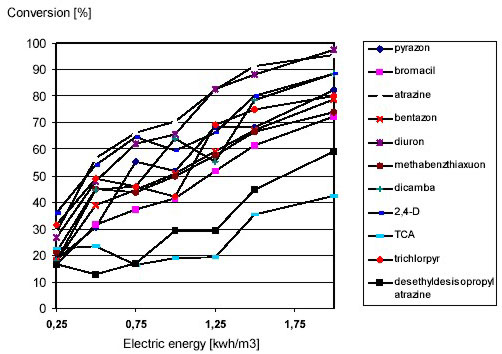

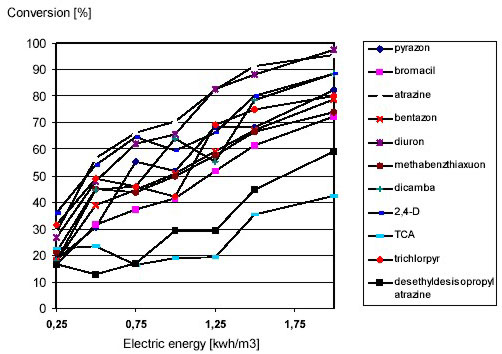

Degradation of 10 pesticides atrazine, pyrazon, diuron, bentazone, bromacil, methabenzthiaxuon,

dicamba, 2,4-D, TCA, trichlorpyr and the atrazine metabolite desethyldesisopropylatrazine by Ultravioletphotolysis

was studied. The electric energy was ranging from 0.25 2.0 kWh/m3 (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Pesticide Degradation by Ultraviolet-Photolysis as a Function of the Ultraviolet-Dose

All priority pollutants showed a significant degradation by Ultraviolet-photolysis. The conversion for an electric

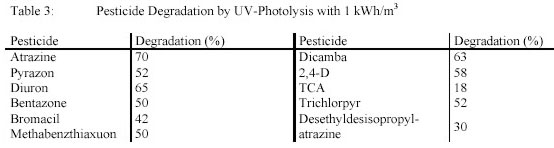

energy of 1 kWh/m3 is summarized in table 3.

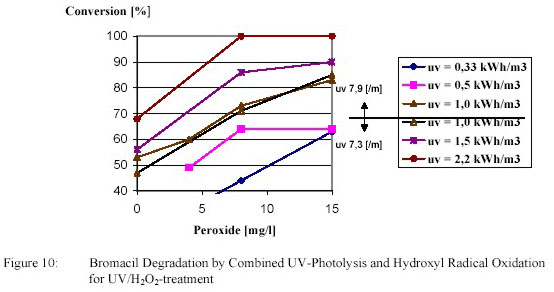

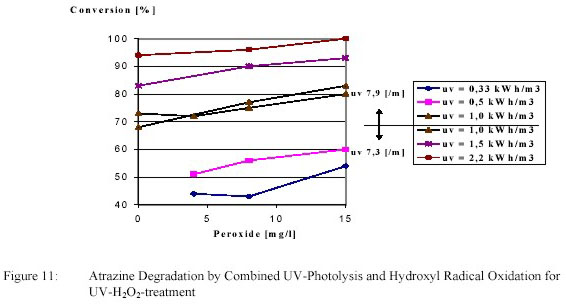

By Ultraviolet-photolysis with 1 kWh/m3 degradation ranged from 18 % for trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to

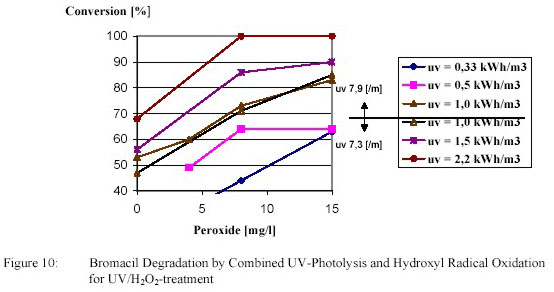

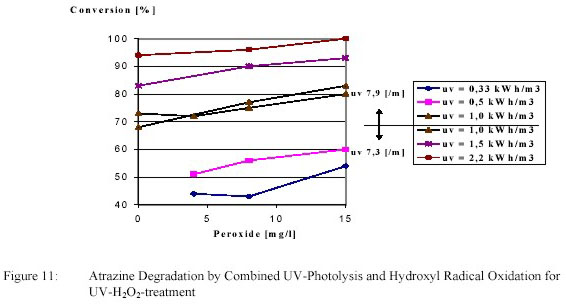

70 % for atrazine. The criterion of 80 % conversion had to be achieved by an additional H2O2-dosage to

initiate a supplementary hydroxyl radical reaction. Examples for a compound with a low and a high Ultravioletphotolysis

conversion are shown in figure 10 and 11.

Degradation of atrazine by an electric energy of 1 kWh/m3 amounted 70 %. This degradation was

increased to the desired 80 % by adding 13 g/m3 H2O2. Atrazine degradation was caused primarily by

photolysis with a polishing effect of hydroxyl radical oxidation.

Degradation of bromacil by an electric energy of 1 kWh/m3 amounted 42 %. This degradation was

increased to the desired 80 % by adding 15 g/m3 H2O2. For bromacil degradation hydroxyl radical

oxidation played a much more important part.

For most priority pollutants a degradation of 80 % can be achieved. Depending on Ultraviolet-absorbance and

quantum yield on the one side and chemical structure (double bonds, H-atoms) on the other side photolysis or hydroxyl radical reactions will play a predominant part. Only for TCA and desethyldesisopropylatrazine 80 % degradation may not be achieved.

PERSPECTIVE

At water treatment plant Andijk Ultraviolet / H2O2-treatment will be implemented. For primary disinfection the

breakpoint chlorination will be replaced by Ultraviolet-disinfection. A dose of 105 mJ/cm2 gives a high

inactivation of phages (viruses) and spores and an complete inactivation of Giardia muris and

Cryptosporidium oocysts. Although some reactivation of Giardia muris cysts is observed, this will not

take place at Ultraviolet-doses as high as 105 mJ/cm2.

Ultraviolet / H2O2-treatment will be implemented for organic contaminant control prior to the two step GACfiltration

already present.

A pesticide degradation of 80 % can be achieved for a broad range of process conditions (i.e. from

0.4 kWh/m3 and 15 g/m3 H2O2 to 0.9 kWh/m3 and 4 g/m3 H2O2). This Ultraviolet dose is much higher than

needed for disinfection. Under these conditions bromate formation is completely absent, while primary

metabolite formation is insignificant.

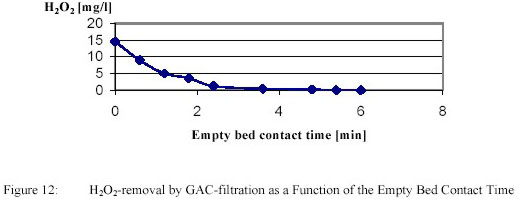

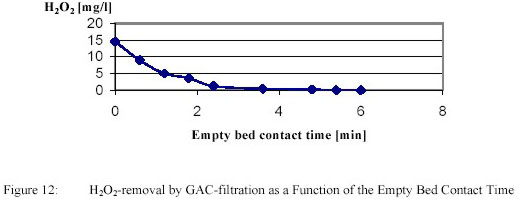

PWN decided to pursue Ultraviolet / H2O2-treatment for full scale application. Important issues were removal of

residual H2O2 and biological stability. Removal of H2O2 by GAC-filtration is presented in

Figure 12.

Removal of 15 g/m3 proved to be complete within 5 minutes. After GAC-filtration with an empty bed

contact time of 40 minutes the biofilm formation rate remained very low (~ 2 pg/cm2.d) during the total

filter run, although AOC increased from 10 to 40 ตg Ac C eq/l.

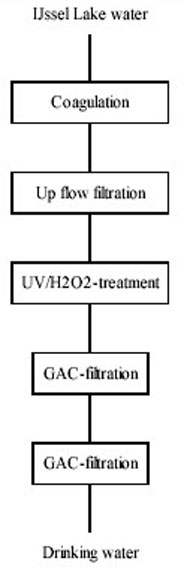

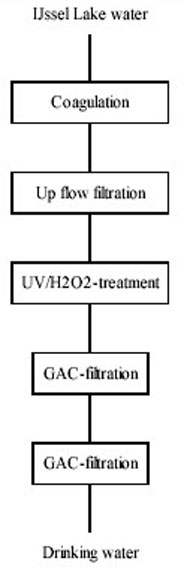

Based on these results PWN will upgrade water treatment plant Andijk to the following configuration

(Figure 13).

Figure 13: Projected Water Treatment Plant Andijk

The combination Ultraviolet / H2O2-treatment / GAC-filtration provides a very reliable and flexible process for:

removal / inactivation of micro-organisms;

organic contaminant control.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank P. Hoogzaad, R. Kooijman (PWN), D.W. Smith, N.F. Neumann, S. Craik (University

of Alberta), M.I. Stefan (Trojan Technologies Inc.) and J.R. Bolton (Bolton Enterprises) for their

stimulating discussions and their assisting in realizing this study.

REFERENCES

1 Kruithof, J.C., Kamp, P.C.: Proceedings IOA/EA3G Conference, Moscow p. 331 348 (1998)

2 Hoigne, J.: Science of the Total Environment 47, 169 185 (1985)

3 Kruithof, J.C., Kamp, Meijers, R.T.: Proceedings 14th Ozone World Congress, Dearborn (1999)

4 Kruithof, J.C., Kamp, P.C.: Proceedings AWWA Annual Conference, Chicago (1999)

5 Sonntag, C. von, Mark, G. Mertens, R., Schuchmann, M.N., Schuchmann, H.P.: J Water SRT

Aqua 43, 201 211 (1993)

6 Bourgine, T.P., Chapman, J.I.: Proceedings IOA/EA3G Conference, Amsterdam (1996)

7 Chang, J.C.H., Ossoff, S.F., Lobe, D.C., Dorfman, M.H., Dumais, C.M., Qualls, R.G.,

Johnson, J.D.: Applied and Environmental Microbiology 49, 1361 1365 (1985)

8 Ransome, M.E., Whitmore, T.N., Carrington, E.G.: Water Supply 11, 75 89 (1993)

9 Rice, E.W., Hoff, J.C.: Applied and Environmental Microbiology 42, 546 547 (1981)

10 Bukhari, Z., Hargy, T.M., Bolton, J.R., Dussert, B., Clancy, J.L.: Journal of the American Water

Works Association, 91, 86 94 (1999)

11 Clancy, J.L., Hargy, T.M., Marshall, M.M., Dyksen, J.E.: Journal of the American Water Works

Association 90, (92 102 (1998)

12 Craik, S.A., Finch, G.R., Bolton, J.R., Belosevic, M.: Water Research (2000)

13 Mechsner, K., Fleischmann, T., Mason, C.A., Hamer, G.: Water Science and Technology 24,

339 342 (1991)

14 Sommer,R., Cabaj, A.: Water Science and Technology 27, 357 362 (1993)

|